By Daniel Goleman and Peter M. Senge

More than three decades of research shows that telling our kids they are smart and praising achievement is not the way to get results. A new article in Scientific American, “The Secret to Raising Smart Kids,” suggests that “focusing on ‘process,’ rather than intelligence or talent, produces high achievers in school and in life.” This process consists of personal effort and effective strategies.

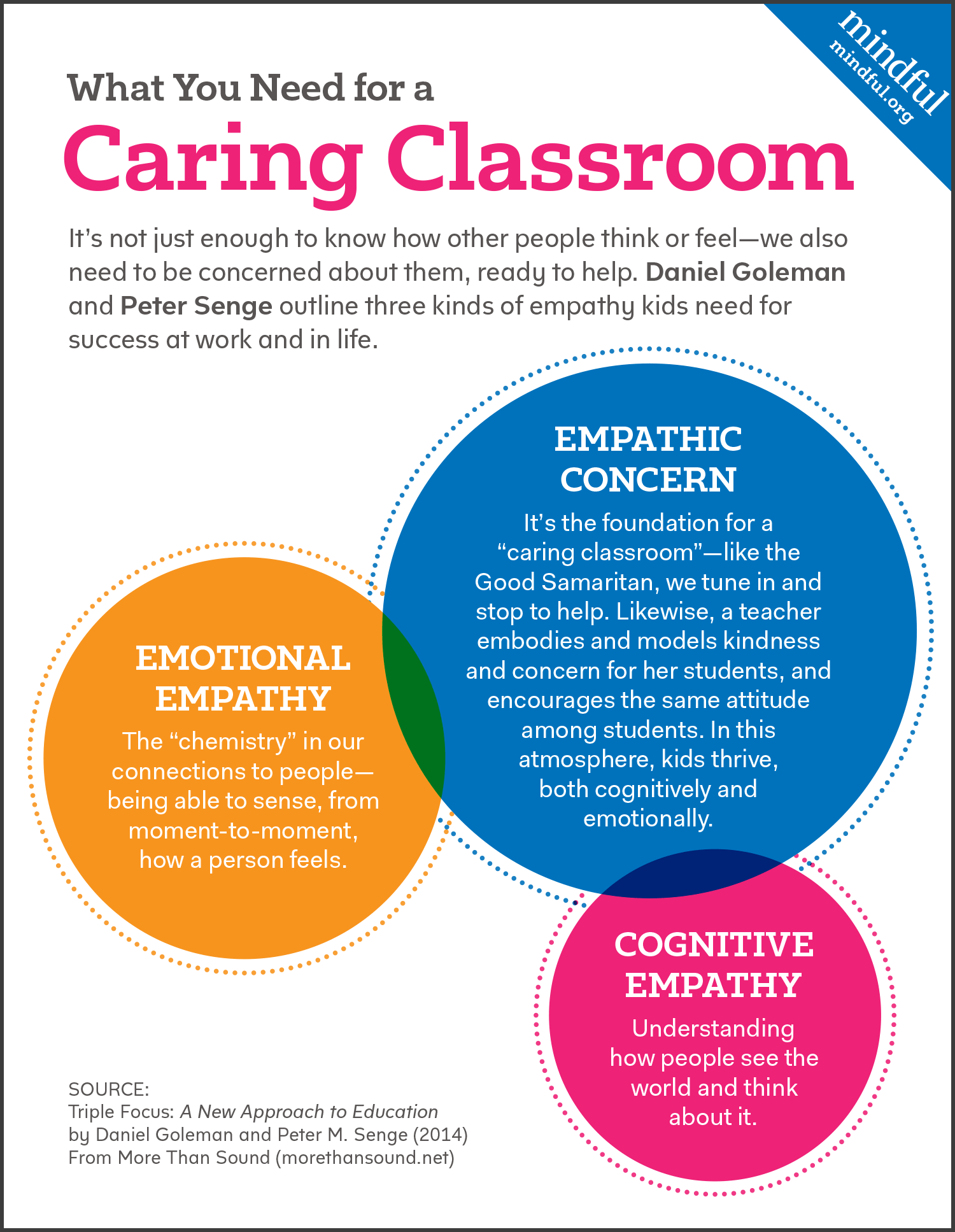

One process we are talking about today is building empathy into the classroom setting, and how developing emotional intelligence is key to success inside and outside of the classroom.

Empathy and Academic Success

The key to compassion is being predisposed to help—and that can be learned.

There is an active school movement in character education and teaching ethics. But I don’t think it’s enough to have children just learn about ethical virtuosity, because we need to embody our ethical beliefs by acting on them. This begins with empathy.

There are three main kinds of empathy, each involving distinct sets of brain circuits. The first is cognitive empathy: understanding how other people see the world and how they think about it, and understanding their perspectives and mental models. This lets us put what we have to say in ways the other person will best understand.

The second is emotional empathy, a brain-to-brain linkage that gives us an instant inner sense of how the other person feels—sensing their emotions from moment to moment. This allows “chemistry” in our connections with people.

Those two are very important of course; they’re key to getting along with other people, but they’re not necessarily sufficient for caring. The third is called, technically, empathic concern—which naturally leads to empathic action. Unlike the other two kinds of empathy, this variety is based in the ancient mammalian circuitry for caring and for parenting, and it nurtures those qualities.

That last type of empathy offers the foundation for what’s been called a “caring classroom,” where the teacher embodies and models kindness and concern for her students, and encourages the same attitude among the students. Such a classroom culture provides the best atmosphere for learning, both cognitively and emotionally.

Learning in general happens best in a warm, supportive atmosphere, in which there exists a feeling of safety, of being supported and cared about, of closeness and connection. In such a space children’s brains more readily reach the state of optimal cognitive efficiency—and of caring about others.

Such an atmosphere has particular importance for those children at most risk of going off track in their lives because of early experiences of deprivation, abuse, or neglect. Studies of such high-risk kids who have ended up thriving in their lives—who are resilient—find that usually the one person who turned their life around was a caring adult.

If you ask them what made the difference, very often they’ll tell you it was that teacher who really saw them, who really understood them, who really cared about them and saw their potential. Such caring and genuine concern is important not just in the classroom but also throughout the school.

Administrators need to care about teachers so that the teachers feel they have a secure base. When you have a secure base, your mind operates at its best. You can function optimally. You can take smart risks. You can innovate and be creative, feel enthused, motivated, and tune in to other people. Compassion comes more easily.

The more upset we are, the more self-focused we become. We tune out the people around us, tune out the systems around us, and we just think about ourselves. Being able to manage your inner life lets you tune in to others with genuine care, and function at your best. It’s true for teachers, for parents, for administrators, and for kids.

Several research centers have been piloting programs that cultivate an attitude of kindness and concern, Stanford and Emory Universities among them. The Mind and Life Institute has created a network of educators and researchers (from these and other institutions) to distill the active ingredients from this research and adapt it into a curriculum for younger students. They plan to start with the first or second grade, and then roll out developmentally appropriate versions for each successive grade level.

For instance, one of the guided reflections a teacher in such a program might lead students through is all the ways other kids are “just like me.” The children would be instructed to consider their common hurts and hopes, their fears and anger, their kindness, and their need to be loved. Such a widened view of how others feel and see the world acts as an antidote to a one-dimensional view of other children that can lead to negative stereotyping or bullying.

One appeal: these are empirically tested methods, and so this program in cultivating compassion should be state of the art. Helping children cultivate their capacity for caring and concern—for empathic action—will likely be the next major step for SEL.

From The Triple Focus: A New Approach to Education. Copyright 2014 Daniel Goleman and Peter Senge. Reprinted with permission from More Than Sound.